- Home

- Corby, Gary

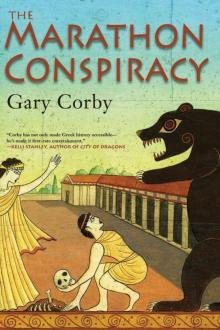

The Marathon Conspiracy

The Marathon Conspiracy Read online

ALSO BY GARY CORBY

The Pericles Commission

The Ionia Sanction

Sacred Games

Copyright © 2014 Gary Corby

All rights reserved.

First published in the United States in 2014

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Corby, Gary.

The Marathon conspiracy / Gary Corby.

p. cm

ISBN 978-1-61695-387-4

eISBN 978-1-61695-388-1

1. Nicolaos (Fictitious character : Corby)—Fiction. 2. Diotima (Legendarycharacter)—Fiction. 3. Hippias, -490 B.C.—Fiction. 4. Private investigators—Greece—Athens—Fiction. 5. Girls—Crimes against—Fiction. 6. Missing children—Fiction. 7. Skull—Fiction. 8. Greece—History—Athenian supremacy, 479–431 B.C.—Fiction.

I. Title.

PR9619.4.C665M37 2014

823’.92—dc23 2013033925

Interior design by Janine Agro, Soho Press, Inc.

Map illustration by Katherine Grames

v3.1

For my own Little Bears, Catriona and Megan

A NOTE ON NAMES

SOME NAMES FROM the classical world remain in use to this day, such as Ophelia and Doris. Others are familiar anyway because they’re famous people, like Socrates and Pericles. And some names look slightly odd, names such as Antobius and Gaïs. I hope you’ll say each name however sounds happiest to you, and have fun reading the story. For those who’d like a little more guidance, I’ve suggested a way to say each name in the character list. My suggestions do not match ancient pronounciation. They’re how I think the names will sound best in an English sentence. That’s all you need to read the book!

THE ACTORS

Characters with an asterisk by their name were real historical people.

Nicolaos

NEE-CO-LAY-OS

(Nicholas) Our protagonist “I am Nicolaos, son of Sophroniscus.”

Pericles*

PERRY-CLEEZ A politician “I suppose you’re wondering why there’s a skull on my desk.”

Socrates*

SOCK-RA-TEEZ An irritant “Nico, I don’t think this can be right.”

Diotima*

DIO-TEEMA A priestess of Artemis, fiancée to Nicolaos “I’ll just hit him again, shall I?”

Allike

AL-ICKY A dead schoolgirl “Allike was one of the smart ones. She could read anything.”

Ophelia

The modern

Ophelia A missing schoolgirl “Why did Ophelia say someone wanted her dead?”

Zeke

The modern Zeke A handyman “It’s obvious I’m too old to be any use.”

Thea

The modern Thea High Priestess of the Sanctuary of Artemis “Age does terrible things.”

Doris

The modern Doris A priestess of Artemis

(the nice one) “What are you doing with that goat?”

Sabina

The modern Sabina A priestess of Artemis

(the bossy one) “No immorality in front of the girls!”

Gaïs

GAY-IS A priestess of Artemis

(the naked one) “Do you know what they drink in Hades? They drink dust.”

Hippias*

HIP-IAS A tyrant He’s dead. Very dead.

Aeschylus*

ES-KILL-US A veteran of Marathon. Also, he writes plays “I write military adventure. That, and family drama like this trilogy I’m doing now. Dysfunctional families slaughtering one another. You know the sort of thing.”

Callias*

CAL-E-US A veteran of Marathon. Also, he’s the richest man in Athens “Don’t push the limits of my bodyguards, Nico. Just point and say ‘kill.’ ”

Pythax

PIE-THAX Chief of the city guard of Athens, future father-in-law of Nicolaos “Dear Gods, boy, didn’t I teach you anything?”

Sophroniscus*

SOFF-RON-ISK-US Father of Nicolaos “I see you’re bent on self-destruction. Well, most young men are, I suppose.”

Phaenarete*

FAIN-A-RET-EE Mother of Nicolaos, future mother-in-law of Diotima “It’s a good thing Diotima is joining us. It’s going to take the two of us to keep you alive. You obviously can’t do it on your own.”

Euterpe

YOU-TERP-E Mother of Diotima, a social climber “I was thinking for the wedding guests, something along the lines of all the best families in Athens.”

The Basileus

BASS-IL-E-US

(origin of our word “Basilica”) The city official in charge of religious affairs “Don’t you have anything better to do than take up my time?”

Glaucon

GLOW-CON Assistant to the Basileus “Record tablets are paid for out of public monies. There’s plenty more where that comes from.”

Melo A forlorn fiancé “I’m not going to shirk my duties just because they’re not official yet.”

Sim A farm manager “If it weren’t for me, Pericles would be broke.”

Ascetos the Healer

AS-KET-OS A doctor “I’ve lost count of how many people have died on that couch …”

Polonikos

POL-ON-IK-OS Father of Ophelia “Take my advice, young man, and avoid both borrowing and lending. These new-fangled bank businesses seem to be springing up all over the place, but frankly, I see no future for Athens in banking.”

Antobius

ANT-O-BIUS Father of Allike “Get out of my way!”

Aposila

AP-O-SILA Mother of Allike “What can I do? Tend the grave of my daughter and care for my family.”

Malixa

MAL-IX-A Mother of Ophelia “I pray to every god that will listen that I will not soon wear my hair like Aposila.”

Blossom A donkey If someone called me Blossom, I’d probably bite him too.

The Chorus

Assorted thugs, slaves, agora idlers, dodgy salesmen, wedding guests, and uncontrollable schoolgirls.

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Author Note

Timeline

Acknowledgments

CHAPTER ONE

PERICLES DIDN’T USUALLY keep a human skull on his desk, but there was one there now. The skull lay upon a battered old scroll case and stared at me with a vacant expression, as if it were bored by the whole process of being dead.

I stood mute, determined not to mention the skull. Pericles had a taste for theatrics, and I saw no reason to pander to it.

Pericles sat behind the desk, a man of astonishing good looks but for the shape of his head, which was unnaturally elongated. This one blemish seemed a fair bargain for someone on whom the gods had bestowed almost every possible talent, yet Pericles was as vain as a woman about his head and frequently wore a hat to cover it. He didn’t at the moment, though; he knew there was no point trying to impress me.

In the lengthening silence, he eventually said, “I suppose you’re wondering why there’s a skull on my desk.”

I was tempted to say, “Wha

t skull?” But I knew he’d never believe it. So instead I said, “It does rather stand out. A former enemy?”

“I’m not sure. You might be right.”

I blinked. I thought I’d been joking.

“We have a problem, Nicolaos.” Pericles picked up the skull and set it aside to reveal the case beneath, which he handed to me. “This case came with the skull.”

I turned the scroll case this way and that to examine every part without opening the flap. It was made of leather that looked as if it had been nibbled by generations of mice. Clearly it was very old.

The case was the sort that held more than one scroll: five, I estimated from the size, five cylindrical scrolls held side by side. The surface on the back of the case was much less damaged than the front, but dry and cracked; this leather hadn’t been oiled in a long time.

I said, “The case has been lying on its back for many years. Perhaps decades. Probably in a dry place such as a cupboard.”

Pericles tapped his desk. “The skull and the case were sent to Athens by a priestess from the temple at Brauron. Brauron is a fishing village on the east coast. The accompanying note from the priestess who sent it said that two girl-children had discovered a complete skeleton in a cave, and that lying beside it was this case. For what macabre reason the priestess thought we’d want the skull I can’t imagine, but the contents of the case are of interest. Open the flap.”

Inside were four scrolls, and one empty slot. I removed one of the scrolls and unrolled it a little. I was worried the parchment might be brittle and crack, but it rolled well enough, despite its age. This was high-quality papyrus, no doubt imported at great expense from Egypt.

I read a few words, then a few more, unwinding as I did. The scroll was full of dates, places, people. Notes of obvious sensitivity. I saw the names of men who I knew for a fact had died decades ago. Whatever this was, it dated from before the democracy. In fact, if what I read was genuine, these notes referred to the years when Athens was ruled by a tyrant, and the author—

I looked up at Pericles, startled.

He read my expression. “I believe you’re holding the private notes of Hippias, the last tyrant of Athens.”

Hippias had ruled many years before I was born. He was so hated that men still spoke about how awful he was; so hated that the people had rebelled against him. He ran to the Persians, who sent an army to reinstate him, so they could rule over Athens via the deposed tyrant. The Athenians and the Persians met upon the beach at Marathon, where we won a mighty victory to retain our freedom.

I held in my hands the private notes of the man who forced us to fight the Battle of Marathon.

There was only one problem, and I voiced it. “But all the stories say that Hippias died among the Persians, after they were defeated.”

“We may be revising that theory.”

“Then the skull is—”

Pericles held up the skull to face me. He waggled it like a puppet and said, “Say hello to Hippias, the Last Tyrant of Athens.”

“Are you sure about this, Pericles?” I asked.

We moved over to two dining couches Pericles kept in the room. He’d sent a slave for watered wine. Now we sat in the warm sunlight that streamed through the window overlooking the courtyard, sipped the wine, and discussed the strange case of a man who’d been dead for thirty years.

“I’m sure of none of it,” he said. “That’s why you’re here. I’m not the only one asking questions. The skull and case were sent in the first instance to the Basileus.”

The post of Basileus was one of the most important, his job to oversee all festivals, public ceremonies, and major temples. A priestess who wanted to bring something to the attention of the authorities would naturally go to him first.

Pericles continued, “The Basileus took it to his fellow archons who manage the affairs of Athens, and they in turn brought it to me.”

I nodded. “Yes, of course.”

It was a strange fact that Pericles, who wielded enormous influence, held no official position at all. The source of his power was that melodious voice, and his astonishing ability to speak in public. Men who would otherwise be considered perfectly rational had been known to listen to Pericles as if bewitched, and then do whatever he said. In the ecclesia, where the Athenians met to decide what was to be done, Pericles needed only to make a mild suggestion, and every man present would vote for it. Conversely, if Pericles disapproved of someone’s proposal, it had no hope of passing a vote. It had reached the point that no one bothered to introduce legislation without first getting his backing. That a man with no official position wielded so much power had become a source of unease among many of the better families, as well as among the elected officials, who were intensely jealous of his easy command.

Pericles said, “It was agreed this had to be investigated, and incredible as it may seem, your name was mentioned. The recent events at Olympia have gone some way to repairing your reputation.”

I’d been unpopular with the archons for some time, ever since I’d accidentally destroyed the agora during my first investigation. One archon had even called me an evil spirit sent to harass Athens, which I thought somewhat cruel.

“Reputation matters,” Pericles said, echoing my own thoughts. “Your standing with the older men will be particularly important.”

I puzzled over that, then asked, “Why, Pericles?”

“Because they’re the only ones who can tell you anything about Hippias. The tyrant belonged to their generation. Not ours. So don’t do anything to annoy them, Nicolaos.”

“Of course.”

“In particular, show the greatest respect to those who fought at Marathon.” Pericles paused before going on. “You know that Hippias was at Marathon, on the Persian side?”

“Yes.”

“The Persians tried to reinstall Hippias as tyrant over us. The veterans stopped them. You must treat the veterans with care, Nicolaos. They’re old men now, and respected, and powerful. The veterans tell a story, that after the battle at Marathon, a signal was flashed to the enemy from behind our own lines. The rumor of a traitor among us has persisted ever since. They say one of the great families of Athens secretly supported Hippias the tyrant.”

“Is it true?”

“How in Hades should I know? That’s your job. I tell you only because this discovery is sure to revive the rumors. We don’t need men finding reasons to accuse each other of treason. We especially don’t need it when the elections are due next month.”

No, we didn’t. The other cities closely watched our grand experiment with democracy. It was in everyone’s interest, not only Pericles’s, that the voting go smoothly and without trouble. If there was any problem at all during the elections, the other cities would say it was because our form of government was unnatural.

Pericles said, “When word gets out about this body—and it will!—everyone will demand answers.”

“Will they? This happened thirty years ago, Pericles. It’s ancient history. Nobody cares.”

“That’s what I thought too. But I was wrong. I’m afraid, Nicolaos, that I’ve made one of my rare blunders. I’ve sat on this skull and these scrolls for ten days and done nothing about them; I didn’t call you in because I thought, like you, that they didn’t matter. But somebody cares. Somebody cares a great deal.” Pericles shifted in his seat and looked distinctly uncomfortable. “I told you two girls found the skeleton.”

“Yes?”

“One of them’s been killed. They say the child was torn apart by some terrible force—”

“Dear Gods!”

“And the other girl’s missing.”

WHY WOULD ANYONE care about an old skeleton, let alone kill a child over it? It didn’t make sense.

I contemplated this as I made my way home. Pericles had no more to tell me. He’d arranged for one of the priestesses—the one who’d walked from Brauron to Athens to report the disaster—to see me at my home that afternoon.

My

family lived in the deme of Alopece, which lay just beyond the city wall to the southeast; Pericles lived in Cholargos, beyond the city wall to the northwest. I had to cross virtually all of Athens to make my way home.

I knew these city streets like most men knew their wives. I knew which of the dark, narrow, muddy paths between the houses were shortcuts—these I slipped down, sometimes forced to edge sideways where owners had extended their houses into the street. I knew which routes ended in the blank wall of a house where some builder had encroached a step too far. Most important of all, I knew which alleys afforded the deep, dark shadows, the ones where the cutpurses and the wall-piercers liked to ply their trade. Those streets were good places to avoid.

I knew these things because for a year now I had been an agent and investigator, the only one in Athens. It was a job that didn’t pay well. In fact, so far, it hadn’t paid at all—Pericles still owed me for my very first commission. Despite my occasional prompts, he’d never quite gotten around to delivering on his end of the bargain. That was Pericles all over. Though he was liberal with expenses when the crisis was upon us, Pericles was a different man when all was calm and the bill arrived. I’d managed to survive so far because my needs were few. I lived in my father’s house, as all young men do, and when I was on a job, I could extend the definition of “expenses” beyond its usual borders. Soon, though, I would have no choice but to corner Pericles and force him to cough up my fees, and for a very good reason: when the night of the full moon after next arrived, I would become a man of responsibilities. I would become a married man.

I entered the city proper through the Dipylon Gates in the northwest corner of the city walls, then walked down the Panathenaic Way, which is the city’s main thoroughfare. The road is paved, which keeps down the dust, and is so wide that two full-sized carts can pass each other without touching. The Panathenaic Way runs like a diagonal slash through the city. I passed by the Stoa Basileus on my right, the building in which the Basileus who had first received the skull and the scrolls has his offices. Opposite it was the shrine of the crossroads, which confers good luck on all who pass through the busiest intersection in Athens. I hoped some of the luck might pass to me; I would probably need it.

The Marathon Conspiracy

The Marathon Conspiracy